Author's note: "The first chapter of my book Chinese Heart of Texas goes into some detail on the Chinese participation in building the [Southern Pacific] into Texas as far as Langtry in 1881/'82. It also contains mention of the earlier Chinese railroad workers in East Texas. I have walked the Chinese railroad camps of the Trans-Pecos and it is a sobering experience for the harshness common to those regions. Until my book no detailed mention of their experiences ever appeared in print other than in a couple of masters thesis here and there."

“JOHN CHINAMAN IS HERE.” A simple four word declaration heralds April 5th, 1875 as that day on which a Chinese person first came to the rustic and rowdy town of San Antonio, Texas.1 Did he remain there for a while, start a business or just look around and leave? Why was he drawn to this oddly cosmopolitan frontier city where so many strange languages were spoken around each corner and in every shop? Ten years after the American Civil War, traveling there from any other town in the state, like Dallas or Houston, required a journey of several days by stage coach. The first railroad did not reach San Antonio until 1877, so that meant a dusty, bone jarring ride for seemingly endless hours and miles.

It will never be known why that first man from China selected San Antonio as a place to explore. Did he like what he saw and find what he was looking for or was he just passing through? Four more Chinese gentlemen arrived a few days later to consider establishing a tea emporium in the bustling town.2 Perhaps they were partners of that first fellow from Canton and were exploring the region’s business potential.

Whatever the answers, this was the beginning of a saga which is significant in its facts, fictions, myths, legends, villains or heroes and the fascinating city that made it important. The old Spanish colonial town had attracted Far Eastern travelers from points unknown. Soon after, a few more of their compatriots arrived and stayed, then others came. San Antonio’s reputation as a good home for Chinese was established.

“Chinamen Spend Jolly Evening in West Side Restaurants” noted the city’s newspaper on January 25, 1906. “The Chinese population of San Antonio assembled in the little restaurants of the West Side Wednesday evening and had a hilarious time until midnight, celebrating their new year.”3 Three decades had passed and a small colony of Cantonese had made themselves at home in the busy heart of Texas. We know very little about them but are fortunate that they remained.

One thing is likely, those men probably did not come to stay permanently. They came to find opportunity, create income, then return to China as highly esteemed successes. This pattern of behavior earned them the title of “sojourners” early in their migrations into California, nicknamed Gum Shan, the Golden Mountain. Eventually, many found that life in Texas also held more promise than did their impoverished homeland.

The majority Sze Yup sojourners came specifically from the four counties of Sunwui, Toishan, Hoiping, and Yanping, of the large Guangdong Province. That made for an unusually cohesive Chinese population in America. This bond helps explain why the late 19th century sojourners were so successful in Texas.

[top]

Chinese may have been in North America for centuries, since they began exploring the Pacific Ocean a millennia ago. A controversial and archaic account suggests that a Buddhist monk named Hwui Shan visited that region we know as Texas about 500 A. D. Maybe so, but the rich and colorful history of the state informs us that the first mass immigration of Chinese was in January, 1870 as 247 men from San Francisco were hired as laborers for $20 a month. Their contract was for helping to complete a Houston & Texas Central Railway line from East Texas to Dallas.6 With completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, their quickly learned talents as graders, blacksmiths, masons and black powder blasters were well established. Those same abilities were needed again, this time in the vast Lone Star State as the great railway moguls competed to put down prodigious miles of track.

A decade earlier, California sojourners who worked on the Central Pacific Rwy. had to pay for their rations when contracted for the rigorous physical labor. In Texas, the men were both fed and sheltered by an eager employer. But that group worked only briefly on the unfinished line in Robertson County near Calvert as prejudice soon caught up with them.

After the first half year of work, immigrant Irish crews refused to associate with the Cantonese laborers who had a three year contract.6 When this occurred, most of the Chinese left the area or state, while some chose to remain. Apparently, Houston’s first actual Chinese resident came from that group and is credited with starting the city’s first commercial hand laundry. Accounts suggest that in early contacts between Chinese and Texans, there was some amount of modest admiration given to the Asians, at least initially.

One newspaperman mentioned that many locals were impressed by the fact that most Chinese then passing through Houston could read and write their native language and were good with numbers as well. The article further stated that “ ... Christian states might possibly learn something from these ‘outside barbarians’ on the subject of national schools.”8 Those first comments are in marked contrast with others which appeared later in Waco and Calvert newspapers during the summer of 1870. By that time, these same Chinese were regarded as “...very lazy, trifling, ....requiring constant watching.”9 This shift in attitude is a bit mysterious but typical of the experience which Chinese found almost universally in their broad migrations.

From another report, we learn that one of these railroaders may have become Texas’ first Cantonese gunslinger. A Houston Telegraph reporter wrote in May of 1870 that when a certain Chinese fellow came to town, he went shopping so as to “go Texas in a big way.” The journalist reported, when “John Chinaman” boarded the train to leave town, he was seen wearing a ten gallon hat, a Bowie knife and a pair of pistols.

[top]

He had been told that area Indians were eager to scalp Chinese men because of their traditional queues, the long braided pigtails all wore then. When he left Houston for camp “.... he was ready for any bad man or bloodthirsty brave.”10 That adventurous sojourner may have seemed an odd sight back at camp among his countrymen dressed in loose fitting, blue cotton trousers and smocks. Surrounded by them, with their felt soled slippers and split bamboo hats, the “Gunslinger” may have stood out but his reputation as a real frontiersman was probably made.

After their contract was broken, most Chinese moved on but some remained. A few then tried to settle in as sharecroppers or found jobs in the ubiquitous cotton fields of the broad Brazos River valley. Others drifted east into neighboring states seeking work. Some settled into the Mississippi Delta region where they helped to establish what became a significant colony which continues today, though more modestly.11 There were a number of other labor ventures for Chinese workers within former Confederate states like Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi in 1870 and 1871.12 These too were associated with railroad projects or plantations; some were successful while others failed due to various disputes.

Occasionally, the initial Chinese presence caused friction with former slaves, the “Freedmen.” A cause for that unrest was apparently due to perceived threats of competition from Asians in the minds of former slaves. That hostile notion, common among Anglo miners, harmed the Chinese in California’s gold fields years earlier. It haunted them again and again in most places where they sojourned in future decades. White planters in some Southern states even tried to exploit this jealousy as a means to control the Freedmen. This duplicity sometimes worked successfully as the Cantonese were used to manipulate another much exploited segment of the population.

The Vicksberg Times of Mississippi wrote during Reconstruction, “Emancipation has spoiled the Negro and carried him away from the fields of agriculture. We therefore say let the Coolies come.” This plan failed when Chinese soon realized that it meant low wages for harsh labor. Most left after being imported in those attempts to supplant African American field hands. Others began modest grocery stores in the rural areas and small towns of the fertile Mississippi Delta region.

Nevertheless, in Texas, the natural industriousness which Chinese initially displayed as agricultural laborers prompted one large plantation owner in Robertson County to import five dozen more in 1874. They went to work in his cotton fields but did not remain for long as again, pay was too low. Most of these early Toishan bachelors eventually left to try and find better wages. A few stayed, took African American wives and had children. The Chinese surnames Yepp and Chopp survive in rural Calvert and Hearne counties of Texas, where the mixed clans were gradually absorbed into the Black population.

[top]

Early regional newspapers gave mention of other pioneer Chinese who were sojourning in Central Texas. Newspaper items indicate that there were two Chinese laundry men doing business in LaGrange through the late 1800s. The town’s Journal proclaimed, “LaGrange is assuming city airs. A Chinese Laundry is being established in the building heretofore occupied by the post office. Two almond eyed gentlemen from the Flowery Kingdom appeared here last week and proceeded to business. They rented the building. . . and made preparations which would seem to indicate that they were in earnest and had come to stay.”

A second laundry followed in 1896, so for a while, the small Czech/ German hamlet in Fayette County had professional Cantonese laundry services. They were apparently welcomed by that early farming community, though the true number of Chinese there remains unknown.

In the Feb. 24, 1888 issue of the LaGrange weekly newspaper, notice was given of “A NOVEL EXHIBITION by the local Chinese Student Company.” This gala affair, to include everything from “Chinese books, photographs, paintings, shoes, ... toys, puzzles, chop sticks, musical instruments, ... opium pipes, and other curiosities” also provided entertainment. What may have been most attractive to more curious LaGrange residents was that “...a Chinese supper with tea furnished by the Chinamen, served in Chinese teapots, etc.” was also on the evening’s schedule.

A more somber episode must be included here as it also relates to Fayette County’s early Chinese. January, 1887 saw construction of the Taylor-Bastrop & Houston Railway into the western part of that county near West Point. An epidemic believed to be yellow fever, decimated the mixed convict and Chinese work crews.

Per practice at the time, the railroad company would have buried the “Chinamen” in a group grave just off the right of way. At the insistence of a local rancher, “Uncle” Charlie Young, these victims were instead buried nearby in his family’s cemetery at Woods Prairie. Family legend holds that it was Young’s belief that this was the “Christian thing to do.” Considering the virulent nature of the epidemic, this was a remarkably compassionate gesture by the rancher. Though these graves remain unmarked, they have been located and are recorded in the cemetery’s formal documentation.

[top]

Thus went the earliest Chinese experience in Texas as these groups came and went without establishing a permanent colony. In Galveston they came closest to doing so when several Chinese hand laundries operated through the 1880s and ‘90s. That colony was wiped out along with the city itself when the cataclysmic hurricane of Sept. 8th, 1900 swept away thousands of people. The ever stoic Chinese survivors volunteered their laundry services in makeshift hospitals, caring for hundreds of the flood’s sick and destitute victims. The old Texas island port might eventually have seen a larger more permanent colony but for the winds of fate.

So the early Chinese railroad men were real pioneers but left little evidence of their troubled era. Later, many more would find themselves in the state and for the same reason, as cheap labor. There was more permanence for many of them in the period which followed. Populations of Chinese first appeared in official census records as the new phase of their Texas history began. First was that of legal immigration while the second period saw the beginnings of “Exclusion” with its growing complexities of migration, lawful or otherwise.

Work on the Southern Pacific Railway’s transcontinental route soon brought 3,500 more Chinese into the state. This project began in the mid-1870s by building through the Mojave desert of southern California then across the Arizona/ New Mexico Territories, and into Texas at El Paso by 1881. As in previous rail laying projects involving Chinese, they proved themselves to be hard working, reliable and cost effective for their employers.

They were not prone to drunkenness or brawling like some immigrant worker groups, especially on paydays, and were generally more healthy. There are two reasons often cited for their stamina, first being their daily habit of bathing after work for the evening meal. Another explanation was their likewise daily habit of drinking only tea rather than whatever fetid water was handy in creeks or ditches. Fresh barrels of the native brew were regularly prepared by their cooks using boiled water. A hygienic beverage was then delivered to the men throughout the day by a “tea boy”.

One more attribute of Cantonese sturdiness was their different diet. Railroad companies generally provided their crews with a mainly meat, potato, coffee and whiskey diet while Chinese had to purchase their own food. They thus bought large quantities of rice, dried commodities like fish, oysters, shrimp or abalone as well as dried fruits and nuts. Their provisions also included noodles, vegetables, Chinese bacon, beans, dried seaweed, bamboo shoots and mushrooms. In general, they ate healthier than their non-Asian coworkers. This meant the Southern Pacific got a bargain in these men and that neither transcontinental lines could have been completed on time without their labor.

[top]

During the era of “manifest destiny”, America’s ambitious railroad corporations competed aggressively to lay track everywhere they could. It enabled America’s westward growth by mainly European immigration. The commerce that went with this spreading civilization meant more railroad business. East bound Chinese crews were matched by a west working force made up of better paid immigrants mainly of Irish and German heritage.

The Chinese labored across vast desert landscapes of America’s southwest with its long hot summers. Northern California track crews had earlier fought extreme winter weather through the rugged Sierra Madre mountains. Many died in deadly avalanches or rock slides, sometimes being buried until the spring thaw. Speculation suggests that hundreds of Chinese laborers were killed in the years it took to complete the first two ocean to ocean railway lines. Small pox took dozens slowly while black powder killed as many, but more quickly. Years later, the Hip Song Tong(fraternal order) saw to it that, where possible, each set of bones was exhumed, polished and sent back to China for traditional burial.

This task was paid for by the Central Pacific Railway Company as guaranteed by the original contracts. Cantonese merchants from San Francisco Chinatown’s “Six Companies” syndicate made fortunes as labor contractors. They worked out the details for hiring thousands of their countrymen needed by America’s railway builders. A southern, ocean-to-ocean route also required several thousand workers. Again, Chinese brokers made big profits by delivering the willingly indentured Sze Yup laborers.

and again in Texas, these track crews were overseen by the able construction superintendent, Mr. James H. Strobridge. The intimidating “...one eye bossee man!” who had lost his right eye to a black powder blast years earlier in the high Sierras. Jim Strobridge was responsible for the Central Pacific’s half of the first transcontinental line. It was joined to the Union Pacific track at Promontory Point, Utah in May of 1869. “Stro” was the larger than life disciplinarian who had driven several thousand Chinese to unbelievable feats necessary for track laying in California, Nevada and Utah.

Strobridge had initially been opposed to supervising any “Chinamen” but he eventually led thousands of them into railroad history books. The Central Pacific’s General Superintendent Charles Crocker needed these men desperately to finish on time. They were often grabbed as soon as they got off boats in San Francisco, then shipped directly to the railhead and put to work. Nicknamed “Crocker’s Pets”, they proved invaluable. Their work assured that congressionally mandated deadlines were met as the railroad companies contractually agreed to do. Congress promised title for thousands of acres of land along the route to the railroad companies and ownership depended strictly on timely completion. Those deadlines were achieved as Chinese work forces made it happen on schedule.

[top]

Crocker even managed to convince Jim Strobridge to use them as masons for tunnel work. He reminded the stubborn Irish rail boss that they had built the Great Wall of China, “...the biggest piece of masonry in the world!” Strobridge reluctantly took on the task of leading thousands of Cantonese and eventually became their staunchest supporter. They seldom disappointed their employers who were literally in a race to meet the U. P.’s west bound track as far to the east as possible. The more ground they covered, the more land they won from “Uncle Sam”.

Ten years later, the vast Chihuahuan desert was equally harsh for the men from Guangdong Province. The Chinese now had extreme heat and high winds, blinding dust storms and possibly, attacks from Indians. Hostile native Americans were one element they had not met while working on the northern line. There, Indians had been “pacified” by the U. S. Army, then bought off by railroad companies with special passes for free boxcar travel across the wilderness.

Still, legend has it that in late 1881, a roving band of Apache marauders murdered all eleven members of a Chinese railroad survey crew near Eagle Pass, Texas.32 This familiar story is included here but is likely untrue, though occasionally cited. The long Texas-Mexico border region remained a violent and deadly frontier well into the 20th century but the Apache threat was eliminated in the summer of 1880. Two costly and decisive battles with the Tenth Cavalry’s famed “Buffalo Soldiers” at Viejo Pass and Tinaja de las Palmas ended the Apache Wars just as the Chinese were getting to Texas.

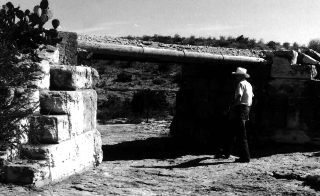

Rancher and historian Jack Skiles of Langtry states further that there is no evidence to document Chinese activity for the Southern Pacific east of the Pecos River. Documentation is available of numerous Chinese massacres in the American West, yet Texas never saw one, at the hands of renegade Indians or anyone else. They certainly suffered though as underpaid laborers and endured much hardship for the sake of their families in China.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Rancher and historian Jack Skiles, shown here, states that there is no evidence to document Chinese activity for the Southern Pacific east of the Pecos River. |

|

|

|

|

[top] |

|

During this railway project, a San Antonio reporter wrote that the Cantonese laborers were worked much like slaves.35 The main difference noted was that they were paid a wage($1.25 per day), half the amount paid to their Anglo counterparts. Treatment from crew bosses was often brutal in their strict maintenance of group discipline. Eye patch wearing Mr. Strobridge was well known for his habit of carrying an ax handle to settle disputes.

By this time in Texas, he respected his Chinese crews for their even temperament, inherent abilities and varied accomplishments. “Stro’s” opinion was transformed as his experience with them increased. He reportedly said once, that Chinese railroad workers were “... the best in the world. They learn quickly, do not fight, have no strikes that amount to anything and are very cleanly in their habits.” He also realized that to insure the peace they had to be kept separate from other ethnic crews both at work and in camp.

For various reasons of prejudice and intolerance, violence was occasionally visited upon the Chinese by Anglo or Mexican track workers. Several men once fled back to El Paso after being attacked and beaten by a Tejano section gang. In January of 1883, a Chinese corpse was found hung from a cottonwood tree on the outskirts of El Paso. The local newspaper referred to them as “... almond eyed heathens”, so their basic human worth was little valued at the time.

Another deadly incident led to an infamous ruling of innocence by Judge Roy Bean for the Irish murderer of a “Chinaman”. The story goes, that after reportedly searching his one and only law book, he concluded “...there ain’t no law in Texas against killing a Chink”.

The Chinese victim did not patronize the “Judge’s” Langtry saloon but the killer was a good customer and thus, could not be antagonized by a guilty verdict. While this Old West anecdote is as much legend as fact, it fits Bean’s sordid reputation. Acts of harmful prejudice were frequent companions for the sojourners from China and would be for many years to come.

Because of this, Chinese workers held steadfastly to their culture and remained a tight knit group, as much as circumstances allowed. Some evidence of this fact survives now, many years after their work was done in Texas’ trans-Pecos region. Shattered remains exist of one of their larger construction camps, which stood in the same location for nearly three months. It can still be found not far from Sierra Blanca some eighty miles east of El Paso and it is mute testimony to daily life for the hard working men from Toishan’s hills.

Crews relocated their camp sites regularly to keep up with track laying progress. This particular camp sat longer because of a need to build an earthen dam. One was necessary to help stabilize the rail bed before ties and tracks could be spiked. 1881 was an unusually wet year for west Texas so a seasonally dry arroyo(drain) stopped the railroad’s advance. Over several weeks, Chinese crews completed the nearly quarter mile long, fifty foot high dam. It survives to the present day and provides Hudspeth County with a shallow lake that is popular with local dove hunters.

Nearby camp areas are still littered with remains of daily life which those men left behind one hundred twenty years ago. They were usually organized into crews of from twelve to twenty men with one chosen as the headman or leader and another hired as the group’s cook. The headman kept daily crew tallies for paydays and maintained general discipline. Each cook’s job was the purchase and management of food supplies, meal preparation and also the daily, continuous brewing of tea for the crew. He had an assistant who helped with meal prep and acted as “tea boy”. Today, one can still find pieces of broken Chinese rice bowls, plates, and cups as well as a cracked wok(cook pan) or two scattered about the desolate ground.

[top]

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Today, one can still find pieces of broken Chinese rice bowls, plates, and cups as well as a cracked wok(cook pan) or two scattered about the desolate ground. |

|

|

|

|

Also found are broken pieces of opium lamps and pipes. More common are busted liquor bottles of ung ka py or mui kwe lu, the potent 100 proof Asian whiskies. There are also Chinese coins and buttons, all laying around scores of stone hearths scattered among the mesquite and cactus. These circles of rock mark many individual camp sites which the men built over an area about the size of a modern soccer field.Some wooden pegs still remain that were used to secure canvas tents under which the men slept.

Also found are small triangular bits of metal the men snipped from the brass lids of opium boxes. These were probably used in playing fan tan on the brief Saturday night and Sunday rest periods which the men were allowed. In the old game of fan tan, “which translates as ‘repeatedly spreading out,’ the bettor tried to guess how many items would remain from a pile after groups of four were removed.” Guangdong natives were very fond of games of chance and gambling. This reflected a traditional Chinese belief that “fate’s hand was at the tiller and life was a gamble. For most nineteenth century Chinese it was better to be born lucky than clever” as one historian has noted.

For some, a more deleterious pastime was also available. Smoking opium was a common practice for some of them. It was an effective, temporary retreat from their daily routine of back breaking toil and homesickness in the wilds of west Texas. In spite of their periodic use of opium and whiskey, the Chinese railroad men were well remembered for their general sobriety and even tempered behavior.

They surely earned any form of relaxation possible after six days of hard work each week. The trans Pecos region quickly impresses one with an overall harshness which those single minded men endured. That entire route was one of empty desert or steep canyons covered by thorny cactus and mesquite. It was infested with rattlesnakes, tarantulas, scorpions and giant centipedes, then usually exacerbated by oppressive heat. But an absolute necessity drove the men to stay on and earn their meager pay. Regular portions of it were needed by their often desperate families back home in the poor villages of Guangdong. Over population, famine and starvation were cruel realities faced by many of their destitute Sze Yup kin.

Chinese were again part of a large army mobilized for a monumental achievement of will and commerce. After much effort and hardship, the Southern Pacific joined the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway about 460 miles from El Paso on January 12, 1883. Following dedicatory speeches, a silver spike was placed and the two lines were united. This occurred near an iron bridge over the meandering Pecos River in Val Verde County. Over the total distance from El Paso to San Antonio, there were 638 miles of track, including 73 bridges, and two tunnels.

[top]

To publicize the completion, San Antonio’s Daily Express published a weekly account titled “San Antonio to El Paso”, by Special Correspondent Hans Mickel. He rode the just finished Sunset Route and filed stories along the way. Mickel’s columns described the rugged Rio Grande canyons, the desolate vistas of far west Texas, etc., and some of the interesting traveling companions he met. On four occasions the writer took time to mention Chinese workmen whom he encountered along the way.

Two of these episodes involved meals that were cooked and served by railroad camp Chinese, much to Mickel’s delight. In the Jan. 30th, 1893 dispatch he said outright “... but it was the best meal I had for many a day and could discount any you can find in a San Antonio hotel.” A third mention suggested that being jostled along in a car full of Chinese who were riding back to the west coast was not all that pleasant. But he continued by saying that on retreating to the caboose, he was confronted by a surly Anglo crew whose company was even less desirable.

Mickel’s column from El Paso spoke of many energetic “Celestials” there who owned shops and stores. The Special Correspondent went on to say that several of them had also gone into agriculture in the fertile river valley along the Rio Grande. He wrote that those growers would soon threaten commercial fruit and vegetable producers of California with real competition.

Most Chinese returned to California when the Southern Pacific job ended. Others found more railroad work in other parts of the state as trunk lines crisscrossed the region. The Texas & Pacific Rwy., built from Fort Worth to Sierra Blanca in 1881 left a small Chinatown at Toyah in Reeves County; it lasted for over two decades. Although the enclave was gone by WW I, the Chinese were fondly remembered for their annually rambunctious New Year’s celebrations. One old bachelor railroader named Sing Lee stayed in Toyah and lived there until the time of his death in the early 1950s.

Another group of Chinese railroad men found work building a line from San Antonio to the border in the summer of 1883. An account says that “about sixty-five Chinamen are in the camp at new D’Hanis.”51 They were supervised by a Captain Hing Chock who had recently returned from China to visit his wife and children. He spoke fluent English, was described as educated and “... a very clever gentleman” who was “... very popular with the people and the gang.” The article goes on to mention that Hing Chock “...and some of his men are inveterate smokers of tobacco while a few used opium. This drug usage occurred especially on Sunday, “but the Captain deprecates its use in unmistakable language.”

[top]

Ten years later, in Jeff Davis County, Chinese were on the job again when a new short line named Rio Grande Northern Railroad was built to serve a coal mine. Joining a workforce of local Mexican laborers, Chinese men excavated a tunnel 135 feet long, twenty-three feet high by eighteen wide. Using pick axes and black powder, they worked through a rugged rock faced hill on the route from Chispa to the San Carlos Mine near the Rio Grande, a distance of 26 miles.53 Low grade coal made the mine economically unfeasible so it was closed and the railroad abandoned by 1897. Used just a couple of times, that tunnel was one of only six ever built in the state.

West Texas has a pair of moderately historic sites that are connected to this great railroad construction epoch. Both of these almost forgotten places are group graves, the final resting places for a few unfortunate Cantonese sojourners. One of these is a grave on the old Mays ranch close to the abandoned coal mine near Chispa. An unknown number of Chinese died there, killed in an accident related to that work, near the Rio Grande.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

In Ector County near Penwell, a second group grave lies within the track right-of-way, just off the roadbed itself. An old homemade cross marks the spot by bearing these words ... “five chinamen died while building railroad .... common grave”. The Texas & Pacific Railway Company has maintained this burial site for the past one hundred and twenty years. The men were buried in a line, head to toe, following a dynamite accident. Nothing else is known about the event yet this grave remains attended on the old but active line. |

|

|

|

|

Apparently, no records of these deaths remain or of how many men ran out of luck in those trans-Pecos wastelands. Some local legends claim that as late as the 1930s, tong workers recovered Chinese remains for shipment back to China. At least one historian states that Chinese graves can still be found in various unnamed town cemeteries in Jeff Davis County.55 Those men’s deaths were a minor inconvenience for their employers but were a great loss for families in far distant Guangdong Province.

Parents, wives and children depended on occasional gifts of money from their sojourner and they held great hope for his eventual return. Some poignancy marks both sites due to the traditional Chinese notion that a man’s bones must rest finally in the ancient homeland if his soul was to find peace. Borrowed here is a page from Maxine Hong Kingston’s fine book CHINA MEN wherein she relates her grandfather’s experiences as a railroad worker in the Sierras. He gave us the final prayer of California’s railroaders, spoken over graves of their many lost friends. Grandfather Hong recalled that the words uttered in their remembrance finished with “. . . and may his ghost have no more toil”.

[top]

We trust that these last words were also recalled by friends of those who perished in West Texas while they helped to construct “the great shining road” out there. How many Chinese died during construction of America’s transcontinental railroad lines is unknown. Some historians say that well over a thousand died while others hold that only a few dozen can be firmly documented. Whatever the number, they were often buried or just covered under rock cairns to the side of track right-of-ways and usually without a marker. In any case, their then unheralded participation in those great projects should never be forgotten or undervalued.

The turbulent post Civil War years saw a prolific expansion of railroads across the continent which brought enormous change to America for better or worse. It was said by many of those involved that Chinese men helped make it possible, so their contributions must be accounted for honestly. Some said at the time that without their labor, the project would have taken many years longer and cost a great deal more than it did. Many thousands of men left China, traveled half way around the world, then worked like slaves to build those American railroads.

That effort alone should surely have earned them full citizenship but it did not. In fact, an ungrateful nation punished them for their mere presence once their usefulness was gained and was no longer needed. The year which saw completion of that great southwestern desert route also witnessed the onset of the federal government’s anti Chinese movement.

The Exclusion Act of 1882 stopped nearly all immigration from China for a period of ten years. The law also made it difficult for American Chinese citizens to leave, travel to China and then return here. As a result of this legislation, gradual decreases in the Chinese population began. That was exactly what the law’s drafters intended but never publicly admitted. Completion of the major railroad projects left thousands of Cantonese without jobs. For those who wished to stay in America, it meant finding a livelihood which did not take work from Anglos or occasionally, Mexicanos. It could be dangerous to do otherwise.

Local newspapers often fomented attacks by publishing virulent editorials and articles meant to inflame public sentiment. Mobs were often led by labor unionists who saw this as an opportunity to strengthen their own organizations.57 In 1882, Chinese were victims of such an attack when an incident occurred at one of their railroad camps near Calabasas, New Mexico. Tucson’s Spanish language newspaper, Las Dos Republicas helped foment the racist violence by stirring up the region’s Hispanic labor force. That camp was destroyed due largely to its presence as a supposed competitive affront to the local work force.

[top]

If they did compete with white men, they did so at risk of lethal acts such as those committed against Chinese throughout California and other western states. The 1880s saw an explosion of hostile encounters which resulted in deaths of dozens of Chinese, most of them miners, cooks and laundry men.59 Worst of these occurred in Rock Springs, Wyoming in September of 1885, when twenty-eight miners were killed and another fifteen seriously wounded by mob violence. That event was followed by anti Chinese riots in Seattle and Tacoma, Washington. Federal troops were called on to restore peace after several killings and much destruction of property in those two Chinatowns.

Chinese men were a ready target for the racist mentality which was common in those times. Fortunately, this was not true in San Antonio, Texas when former railroaders began moving into the growing town. Arriving there, they fit in as still another patch in the colorful ethnic quilt of an immigrant metropolis.

The city was experiencing great growth by 1880 since the arrival of the first Eastern railroad line just three years earlier. Perhaps due to the prosperity, Chinese did not represent an economic threat so their services were welcomed. As their numbers increased they were never met with the overt hostility which was then occurring elsewhere. This allowed for a more peaceful entry into an already diverse mosaic of cultures which the city abided. The earliest Cantonese settlers there fit in smoothly by the late 1870s. When many recently unemployed railroaders arrived by the middle 1880s, they too were casually absorbed into the modest melting pot. As San Antonio became a terminus for the Southern Pacific Railway line, it also became a destination for Chinese sojourners.

Book Description From the Author's Website

Chinese Heart of Texas: The San Antonio Community (1875-1975) is one hundred years of history and one hundred years of pride. This is the vibrant story of why and how the Chinese came to Texas a few years after the American Civil War.

Most importantly, Chinese Heart of Texas is about what enabled the Chinese to stay at a time when they were being driven out of many other places. No ethnic group faced the unique struggles and prejudices which confronted them as they chose to become Americans, and no other group of people met those challenges quite so well and with as much success as did the sojourners from ancient China.

San Antonio became a good home when its own uniqueness provided acceptance and opportunity. The detailed telling of this tale is here along with many previously unpublished photographs.

Large stories and small ones combine to make a colorful mosaic of Chinese trials and triumphs -- from being unwanted aliens to ordinary citizens. Some became respected physicians or prosperous businessmen while others became decorated soldiers, sailors and airmen.

While the Chinese were becoming Americans and Texans in every sense, they produced a century of history rich with texture, important in scope and remarkable by example. |

|