SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT. In the near future, in a supplemental report, we shall state the facts in relation to all the other tap lines whose affairs are disclosed on the record before us, and shall point out which of them are regarded by the Commission as common carriers in the service that they render to their respective proprietary companies. The cancellations by the trunk lines will be allowed to become effective on May 1 as provided in the tariffs now on file. The rights of such tap lines as we find, in the supplemental report, to be common carriers will be protected in the order that will be entered herein in connection with the supplemental report.

PROUTY, Chairman, concurring:

While I do not dissent from the conclusions finally announced in the majority opinion, I do dissent from the implication that the building of branch-line railroads, whether denominated tap lines, industrial lines or what not, by those persons who own an industry to be served by these railroads, should be discouraged by this Commission While the industrial line and the tap line have been the medium through which the grossest discriminations have been perpetrated in the past my belief is that these unlawful practices can be stopped without the slightest difficulty and that the thing itself should be encouraged rather than discouraged. This view, which I have entertained from the first, is confirmed by observation and reflection, and I desire to keep it clearly before the public.

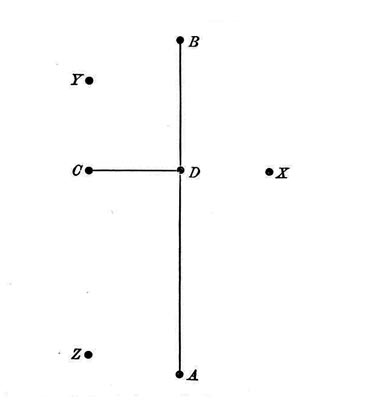

Let us assume that AB is a 100-mile section of a trunk-line rail-road and that CD is a branch extending from C to D. The section traversed by this railroad produces lumber, coal, stone, perhaps various commodities. The principle is the same in all cases, although the application might somewhat differ.

X, Y, and Z are localities distant from the main line by about the same number of miles as C, but in these localities the industry has not been developed.

The railroad AB applies to all points upon its main line and to its branch line CD the same rate to markets of consumption. X, Y, and Z can not be developed until railroads are constructed, connecting these localities with the main line. Manifestly it is for the public interest that connecting lines shall be constructed, since otherwise a monopoly in the production of the commodity at points tributary to AB is possible. By whom shall these branch railroads be built?

Manifestly the owners of property at X may construct a road from X to AB and may transport the commodity manufactured from X to AB and there ship it to destination. The cost of rendering this service may be, if lumber, 3 cents per 100 pounds; if coal, 10 cents per ton. Whatever the cost, it is plain that the operator at X is at a disadvantage as compared with the operator at C by the exact amount of this charge, and it frequently and perhaps usually happens that the advantage thereby obtained by the industry at C is sufficient to entirely prevent, certainly for a long time, the development at X, Y, or Z.

The inevitable conclusion is that the railroad AB absolutely dictates the development of this region. If it elects to construct its branch line to C, that locality becomes valuable, whereas if it goes to X or to Y those are the favored locations. It must be admitted that it is most unfortunate to put the development of a country into the hands of a mainline railroad as this of necessity does. My own belief is that those persons interested in the localities other than C should be permitted, where circumstances justify, to construct a railroad from X to the main line; that the main line AB should be required to establish in connection with the branch line from X the same rate which it applies from its branch line at C., and should be required to accord to the branch line in the way of a division a sum which is fairly equivalent to the expense which it incurs in originating this traffic at C and handling it from C to D. This is certainly in the public interest; what valid objection can be urged against it?

Consider this, first, from the standpoint of the main-line rail-road that road transports the traffic from C to D at a certain cost and from D to destination at a certain other cost. If from the through rate there be deducted the cost of transporting the business from C to D, there remains the service from the main-line point D to destination. If, now, it allows the other branch line from X the same amount, it becomes a matter of indifference, so far as its profit as a railroad is concerned, whether traffic originates upon its own branch line at C or upon the independent branch line at X.

This might be urged, possibly, that if the mine or the forest at X is developed the mine or the forest at C may produce less, and the main line may therefore have less business for its own branch; but this is a, matter of small consequence, which ought not to weigh in the general conclusion. Its profit is not made upon the branch line but upon the main line.

If this railroad AB itself owns lands at C which it desires to develop, then manifestly it is for its advantage that the branch line from X should not be constructed; or, if those persons interested in the main line and potential in the direction of its policy own lands at C, it is manifestly for their interest that no other similar industry should be developed; but the function of a railroad in these modern days has come to be, not the exploitation of its private property used in other than its transportation purposes nor in the enriching of those who sit in its directorate, but rather in serving the entire public impartially and for a reasonable consideration.

From the standpoint of the main-line railroad, considered purely as a railroad, there is no reason why the branch line from X should not be permitted to connect and should not be allowed a suitable division. It should be carefully noted that this only applies in its entirety to instances where the main line establishes a blanket rate upon its main line, as is usually done with producing points in case of lumber, coal, etc., and where it extends that rate to its own branch lines. If a fair mileage scale were applied, both to main line and to branch line, these difficulties would largely disappear. My proposition only goes to this : That the main-line road should be required to put the industry at the end of the independent branch line upon substantially the same basis that it puts the industry at the end of its own branch line or at a corresponding point open its main line.

Consider this matter, now, from the standpoint of the mine or the mill. Compare the operator at C with his competitor at X.

The distance from the main line to C is the same as from the main line to X. There is no reason why the rate from X ought not to be the same as the rate from C. Suppose the same rate is applied and is paid by both these competing operators. Looking to the mill and to the company which owns and operates the mill, manifestly there is no discrimination.

But it is said that the same individuals who own the industry at X also own the capital stock of the railroad which leads from X to the main line, and that therefore they have finally the benefit of whatever division is allowed to this independent branch line.

This branch line is performing a legitimate common-carrier service, exactly the same service from X which is performed from C. The agency which performs that service from X is entitled to a fair compensation to exactly the same extent as is the agency which per-forms that service from C.

If, now, the expense of constructing and operating the railroad from X to D is such as to leave no net return out of the divisions allowed by the main line, then the individuals who own the mine at X have received nothing beyond that received by those who own the mine at C, although they have invested and devoted to the public service an additional amount of capital. If the net is sufficient to pay a fair return upon the fair value of the property, they have received exactly that to which they are entitled under the constitution of the United States.

The mining company is not discriminated in favor of, for it pays the same rate as does the competitor at C. The individuals who own the railroad from X to the main line are not discriminated in favor of as against the individuals who own the mine at C, for they have only received a legitimate return upon the property which they have devoted to this public service, if it be a legitimate public service. It is true that if the division allowed to the independent branch line is excessive, that does work out a final discrimination, not in favor of the mine at X, but in favor of the individuals who own the railroad and who also own that mine. The discrimination would be exactly the same if the divisions were, with respect to traffic, not produced at the mine, but handled from the mine of a competitor upon the branch, or with respect to an entirely different species of traffic.

it is urged that this gives to the owner of property at X an ad-vantage over the owner-of similar property at Y, and this is true, for neither X nor Y can be developed without a railroad. But that sort of discrimination arises out of the fact that the operator at X has the money or the means of securing the money with which to build the railroad from X to the main line, while the owner at Y does not possess this means. Some day the importance of this aspect of the case may become such that the government itself will build and operate all these branches, but until then the most that can be done is to secure to all persons equality of opportunity, to give to the individual at Y, if he can find the money, the same chance which the individual at X possesses.

In my opinion, this right to build branch lines and obtain recognition from the main line is becoming daily of more and more consequence. Our trunk lines have been built; many, perhaps most, of the branch lines remain to be built. Upon what inducement is this future development to take place?

In the past branch lines have been often constructed to develop properties which the railroad itself owned; still more frequently to develop properties owned by those who could influence the policy of the main-line railroad.

Branch lines have often been constructed as stockjobbing propositions with a view to selling them at an extravagant price to the main line. These motives will not to any great extent operate in the future, and if there is to be a free development of our resources, if that development is not to be put entirely under the control of our railroads and the influences which dominate them, then the recognition of branch lines by the main line must be enforced.

It is significant that the three states in which the tap lines under consideration are most developed Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas in every instance approve and insist upon the legal status of these railroads, the reason being, as stated by their accredited representatives before this Commission, that the recognition of the tap line promotes the development of the country by fostering the building of railroads which will otherwise not be constructed and which the country absolutely needs.

It is desirable that common carriers by rail should be strictly confined to their public functions and not permitted to engage in private commercial pursuits. While this may not be as imperative in case of branch lines as with trunk lines, since the former can be subjected to a closer scrutiny and a higher degree of control, still the ideal condition would be one in which the carrier's service was performed either by the government or by some private corporation with no interest whatever in the property transported. We should not, how-ever, sacrifice the essential to the pursuit of the ideal, nor should we repress legitimate undertaking simply because some phases of the means employed may result in abuse. Congress might prohibit all connection between railway and private industry. As to what has actually been done, it may be observed:

First. When Congress came to declare its will in this respect by the enactment of the commodities clause, lumber was expressly excepted from the operation of that provision, thereby giving an implied sanction to unity of ownership between the lumber-carrying railroad and the commodity which is carried.

Second. The commodities clause itself as interpreted by the Supreme Court and as accepted by Congress since that interpretation does not prohibit a common ownership of industry and railroad, provided the two are kept entirely separate and distinct in their operation. Inasmuch as the statute has not been changed since that interpretation was put upon it, it must be assumed that as so interpreted it represents the legislative will.

The abuses disclosed by the present proceeding result mainly from two causes:

(a) In many cases divisions are allowed on account of so-called railroads which are in reality mere plant facilities. Of the 83 cases now before the Commission, a majority are of that character.

I do not attempt to define here a railroad. I do wish to say, how-ever, that the basic inquiry is not, in my opinion, whether the operation is great or small, but rather is it honest. Does it occupy the sphere of a railroad?

If public necessity requires that this railroad be built and operated; if, under the laws of the state in which it exists, land can be taken in invitum for its right of way; and if the railroad itself is, in fact, operated and maintained as a public carrier in conformity to the laws of the state which creates it, and of the United States in so far as it is subject to federal regulation, then I think it must be treated as a public servant, irrespective of the amount or the character of its traffic.

If a particular railroad is found to be a common carrier by rail-road, under the act to regulate commerce, then I think, irrespective of its stock ownership, without reference to the purpose of its creation, it must be treated as such; that in all cases the trunk line may establish joint rates and allow proper divisions of those rates and, in many cases, it should be compelled to do so.

(b) In many instances where the allowance of a division is proper the division itself has been excessive, and this, without doubt, has inured to the benefit of the industry or of the persons or individuals who owned the industry. While there may be some doubt as to our authority in the premises, I believe we have the right to determine in these cases whether the divisions are excessive and to order them reduced to a proper amount.

If this Commission prohibits the payment of any division in all cases where the railroad is not a bona fide common carrier, and con-fines those divisions when properly allowable within proper limits, I am unable to see how harmful discrimination can result.

One fact has been developed which does lead to slight discrimination and which we can not apparently correct, and that is the issuing of passes to the officers of these common-carrier tap lines who are also owners and frequently officers engaged in the management of the industries. The use of these passes when traveling upon the

business of the industry undoubtedly gives to that industry an advantage over its competitor.

This is wrong and should be corrected if not by the voluntary action of the carriers who issue and honor these exchange passes, then by Congress. But let it be noted that this vice is not confined to the insignificant tap line. Directors of main-line railroads are almost invariably engaged in private business, in the course of which free transportation is used.

Discrimination of this kind ought not to exist, but it will continue to exist until common carriers by rail are prohibited from issuing these exchange passes. When the issuing of free transportation by railroad is restricted to railroad employees who spend substantially their entire time in railroad service, with such general exceptions as may be made upon sentimental grounds and which involve no element of commerce, discrimination from this source will cease, and not until then.

I do not wish at this time to enter upon any general discussion of this tap-line question; that I have done in previous reports; but only to restate my conviction that to prohibit or discourage legitimate enterprises of this character is to deal a serious blow to the future development of this country.

I may add that I do not fully concur in the suggestion that main-line carriers may make to the owners of private railroads not common carriers allowances for the movement of lumber from the mill to the main line. I doubt whether this is a transportation service within the meaning of the fifteenth section; but even if the allowance might be under some circumstances lawful, we ought not to invite it.

There is no essential difference between a private railroad operated by steam and a tramway or a dray. When once the door is opened there is no stopping place. I believe that all these services should be performed by the railroad itself and that the shipper, instead of receiving an allowance for these accessorial services, should be compelled to pay a reasonable charge for every service rendered outside the ordinary transportation. |